What It Takes To Be An Advantaged Acquirer

March 31 2016

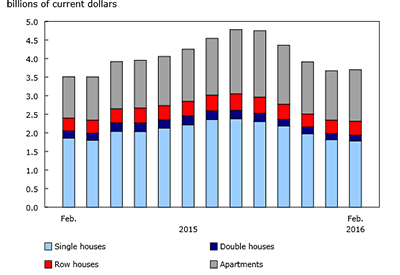

Last year was one for the M&A record books. As of the end of 2015, some US$3.8 trillion had been spent on mergers and acquisitions — the highest amount ever — according to data compiled by Bloomberg[1] and while M&A may not continue at this record pace, the trend seems far from abating. Many companies, in fact, intend to continue coupling in 2016 for numerous strategic reasons, including expanding in existing markets and scale efficiencies, reports the most recent CFO Signals survey.[2]

Still, this type of volume indicates that we may be in a “merger wave” — concentrations of accelerating M&A activity — possibly the sixth so far in the last century.[3] And while time will tell if we have crested it or not, this type of heated pace can produce mistakes, such as deals that don’t achieve the anticipated benefits or fit strategically with the acquirer. Moreover, premiums acquirers agree to pay over the target’s pre-bid share price tend to escalate as competition intensifies.

Amid such deal exuberance, it may behoove CFOs to not only become an acquirer, but to become an advantaged acquirer. After all, several factors that have been driving M&A for the last few years—low interest rates, accessible and inexpensive financing, healthy balance sheets, and an economy that’s growing at less than 4% — remain intact [4]. To win in this environment may involve something more: a set of detailed action steps that helps companies identify strategic deals instead of simply reacting to the spate of available deals and auctions. In this issue of CFO Insights, we will examine the common mistakes that happen in merger waves and outline ways that CFOs can potentially avoid them by becoming advantaged acquirers.

Merger wave challenges

Merger waves happen when deal volumes increase dramatically, crest, and then fall. In short, companies start making capital investments they were not doing in prior periods. The first such period began in the 1920s and ended with the Great Depression. Subsequent waves happened in the 1960s and in each decade since the 1980s. While the reasons behind those waves vary, there are several mistakes that companies often make in these periods.

The first is having an unclear growth strategy or one that does not clearly consider the role that M&A will play in that growth. In the M&A space, that can push companies into being reactors. Unwittingly, they have outsourced their growth strategy to the investment bankers and often end up reacting to the available deals those intermediaries present instead of proactively identifying viable candidates through their own strategic process. While this is very common in the M&A landscape overall, it tends to be magnified during merger waves, as more inexperienced acquirers enter the arena and experienced players expand their risk profiles.

Overpaying is another mistake that often happens as deal volume escalates. Academics Peter Clark and Roger Mills argue that there are four distinct phases of merger waves.[5] As reflected in prices, bid premiums in phase one have averaged just 10%-18% during merger waves since 1980, rising to 20%-35% in phase two, reaching beyond 50% in phase three and even over 100% in the fourth and final stage where many ill-advised and costly deals are struck — often leaving a legacy of broken promises and lost value.[6]

The third challenge is simply a lack of options. With the Presidential election looming and continued market volatility, there is concern that the economy may not be the driver of corporate growth that many had hoped. In such an environment — and often at the urging of activist shareholders — companies may turn to deals in an effort to increase shareholder value simply because they believe they have no other choice. Given how common deals have also become in certain industries such as consumer products, technology, and health care, various stakeholders, including investors and boards, may also favour them over organic growth or other options.

Characteristics of the advantaged acquirer

It is well documented that a large percentage of M&A transactions do not deliver the value promised at the time of the deal.[7] Those that avoid this fate — particularly during merger waves — tend to be those that have a disciplined process that allows them to find good opportunities and avoid poor ones, thereby maintaining a competitive edge and delivering shareholder value. The tenets of that process typically include the following.

1. Self-assessment. It’s important to first assess, as CFO and the C-suite, your strengths, weaknesses, and opportunities for growth, both in revenue and value. That can include deciding which customer segments and associated geographies you want to serve, how you want to do so in ways that competitors cannot easily replicate, and then understanding the capabilities and market access that will be required to achieve those goals. Essentially, you want to consider developing a strategy that outlines how you’re going to complement your strengths and backfill your weaknesses. If you haven’t gone through that process, you’ve likely trapped yourself into being a reactor in M&A.

2. Identified priority pathways. Advantaged acquirers who have done such a careful assessment know what their priorities are for M&A. In other words, they know if M&A is going to make up 10% of their growth or 20% or more. As part of the process, they likely have also identified their priority pathways at the business-unit level that address the new product or solutions they will bring to market at prices that will add value for customers. After all, corporate-level growth expectations can be de-averaged to business-unit level and used to highlight gaps and prioritize the role of M&A across those units. Without that prioritization, you can expect to face a reactive political process on which potential deals are in the best interest of the company.

3. Competitor signalling. It’s very important to also look at the strategic intent of your competitors. There’s often a lot to learn from examining the deals your competitors have done over the last several years, in terms of geographies, capabilities, size, and customer segments. Call it competitor signalling. Their past behaviour will often determine which targets may be next on their priority lists. And armed with that information, you can often determine if a deal does or does not make sense for you relative to what competitors are signalling in the market—and your own strategic priorities.

4. Strategic screening. Once the universe of opportunities is identified, advantaged acquirers strategically screen them. While M&A strategy helps develop prioritized pathways for growth, target screening filters the deal universe in those pathways to help generate portfolios of priority candidates. Those filters may include everything from size, geography, and customer segments to technology and management talent. Management may debate what those strategic priorities are along those pathways. But the filters are actually important strategic choices that can help senior management and the board understand why a particular priority target was identified in the first place. And as one Fortune 100 executive told us, “The more you look, the more you find; the more you look, the more you learn; and the more you look, the more you test your strategies.”

5. Disciplined execution. Finally, there are typically two sides to executing a deal — transaction execution and integration. With the transaction, there are the identification, pricing, and prioritization that need to get done. But equally important is the ability to integrate. As an advantaged acquirer, you should consider what potential culture clashes, labour disputes, and distribution gaps might exist with a particular deal and factor them in the screening process. It can be nearly impossible to analyze synergy potential or conduct a sensible high-resolution valuation without evaluating such integration risks. With the risks identified, though, you can often differentiate opportunities by integration issues and determine if you have the right resources and talent to integrate effectively.

Bringing discipline and patience

In our experience, advantaged acquirers use this dynamic process to develop a watch list of opportunities that is continually refreshed —and tend to close a small fraction of the deals on that list. As long-term successful acquirers, they are talking to and negotiating with companies regularly, but only pulling the trigger on deals that fit their overall strategy at appropriate valuations. In addition, their CFOs typically bring both discipline and patience to the process.

Specifically, as stewards, CFOs determine if the deal fits that strategy. And they often do so by sticking to their defined rationale and not becoming so enamored that they do something that could harm the company. Moreover, they help bring discipline to the process by bringing together the right people in finance, strategic planning, and human resources to make sure the acquired assets are integrated properly. Finally, they wield patience by having alternatives in case anything goes awry.

Along the way, these CFOs are often guided by several common questions:

Are we looking at the right deals? If you’re going to be advantaged, you’ve got to know what you want to buy. Getting there effectively involves understanding the universe of opportunities so you’re not in the position where an investment banker or seller brings you a deal you haven’t thought about.

Have we measured the potential impact on ourselves — and our competitors? Having a strategy that not only measures how a target fits into your strategy, but also how it could hurt that strategy if the target was acquired by a competitor can be imperative. There may be times when it is in your best interest for competitors to move in because of the time it will take them to integrate or the limited strength the acquisition gives them in certain markets. But you are likely going to consider that only by applying scenario planning to the M&A landscape.

Do we have the appropriate integration capabilities? It’s often the financial team’s responsibility to not only identify what financial resources are going to be allocated to the transaction, but also what talent. What talent is needed to integrate the target properly? Can we execute this strategy with the resources we have?

What can we walk away to? With every deal, there should be some best alternative. As premiums rise, CFOs should be in a position to decide if it is better to buy at 50 times earnings or walk away and do something else with the capital. Without alternatives, you will likely find it difficult to walk away.

Many CFOs complain that they have trouble finding quality assets on the market. One of the other common advantages of being an advantaged acquirer, however, is that those quality assets will typically find you as you uncover the universe of opportunities in the market. Once you’ve done the self-assessment, the strategy development, the identification, and prioritization of targets, the viability of a particular deal can become increasingly clear. And if a deal does not meet the parameters you’ve built, then there is often the option of walking away to other high-priorities deals that you have on your watch list. There may be another deal, or you can reapply the funds to other more important segments of the business. After all, advantaged acquirers can afford to be patient—they know what they want.

Endnotes

1. “2015 Was Best-Ever Year for M&A; This Year Looks Good Too,” January 6, 2016, Bloomberg; www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-01-05/2015-was-best-ever-year-for-m-a-this-year-looks-pretty-good-too.

2. CFO Signals, Q4 2015; www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/finance/articles/cfo-signals-survey-executives-sentiment-betting-america-despite-concerns-2015q4.html.

3. “Riding the wave,” The Economist, www.economist.com/news/business/21587207-corporate-dealmakers-should-heed-lessons-past-merger-waves-riding-wave, October 2013.

4. “National Income and Product Accounts: Gross Domestic Product: Fourth Quarter and Annual 2015 (Second Estimate),” Bureau of Economic Analysis, www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/gdp/gdpnewsrelease.htm, February 2016.

5. Masterminding the deal: Breakthroughs in M&A strategy and analysis, Peter Clark and Roger Mills, Kogan Page, August 2013.

6. Masterminding the deal: Breakthroughs in M&A strategy and analysis, Peter Clark and Roger Mills, Kogan Page, August 2013: (Original source of acquisition purchase premium (APP) percentages, Beyond the Deal: Optimizing Merger and Acquisition Value, see pp 20-23, 47-54; Harper Business, 1991.)

7. “Integration report 2015:Putting the pieces together;” Deloitte LLP.

This article was first published as a Deloitte CFO Insight. These insights are developed with the guidance of Dr. Ajit Kambil, Global Research Director, CFO Program, Deloitte LLP; and Lori Calabro, Seni. For more information on Deloitte’s CFO Program, visit www.deloitte.com/us/thecfoprogram.