Bob Shapiro: Playing the Hand You’re Dealt

Imagine starting a business where one of the largest independent players, which you used to work for, actively discouraged suppliers from doing business with you, limiting the products you could get your hands on. Imagine that your place of business didn’t have doors big enough to fit the very things you were selling. Cashing in your chips would not be unreasonable thing to consider, but it’s not what Bob Shapiro’s father did when he was trying to get Franklin Electric off the ground in Montreal in 1946.

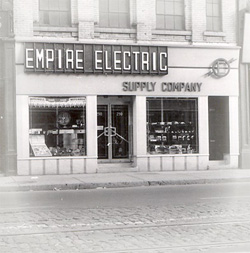

“My dad had worked for Union Electric for 17 years. They were the largest independent electrical distributor in the country and they had reneged on some promises, so he left,” explains Bob Shapiro, president of Franklin Empire. “But they wielded a couple of big sticks and they discouraged suppliers from doing business with my father.”

With suppliers under threat, and wartime material quotas still in effect, the elder Shapiro would sell fishing rods and anything he could put his hands on. “The place of business my father set up, neither the stoves nor fridges could fit through the front door, so having started the business with a brother, one brother would stay with the fridge or the stove outside and the other brother would go try and sell it somewhere.”

Bob Shapiro’s first job was with IBM in 1965, selling computer systems. A graduate electrical engineer, Shapiro learned a lot about computers but he also learned a lot about how to do professional sales. Then in 1968, his father became ill, and Franklin Electric employees recruited the young Shapiro to help. “I went out as a salesman. I knew nothing. Trust me, I knew nothing but I went out as a salesman.”

His father recovered and the two worked together for 20 years. The son would eventually take his father’s place as president in the mid-80s, going on to oversee the acquisition and eventual merging of specialty distributor EW Playford. In 1992, Franklin Playford merged with Empire Electric, becoming Franklin Empire.

Now, Franklin Empire supplies electrical components for new construction, renovation and the maintenance of industrial plants as well as residential and commercial buildings. They specialize in automation systems for manufacturing processes, and are the only full-line electrical distributor with manufacturing and repair services. They employ somewhere in the neighborhood of 450 people, have over 20 branch locations in Quebec and Ontario, including their five assembly and repair divisions.

Shapiro’s two partners are the Backman brothers, Bernie and Cliff, who are from the Empire Electric side. Bernie’s three children are in the business, too, and according to Shapiro, “It’s going very well because they are hardworking kids and they take nothing for granted.”

It brings up the question of succession. “My father did it very well and he did it almost by chance because he was a very nice guy,” he says. “And the fact that I had worked and had success elsewhere before I came into the business, I don’t think many of the employees felt imposed upon. If the baton is being passed by the creator of the business, very often when they bring family in they give them responsibility but without authority. ‘You do whatever you want, Bob, but check with me first.’ And you have to be careful not to fall into that trap,” he explains. “You also have to recognize that if the family that you’re trying to pass the baton to doesn’t have the skillset. Then go get professional management and let them be the mentors of your children if your children are willing.”

The Biggest Business Challenge

The road to success is naturally paved with speed bumps. And while Franklin Empire doesn’t have to deal with wary suppliers or doors that are too small anymore, the business challenges are nevertheless there. “The biggest challenge is people,” Shapiro says. “Recruiting people, training people, retaining them. Certainly the 20s- early 30s generation of today don’t have the patience I would hope for.

“The reality is this. If a person stays in the job for three years you’re doing well and if they stay for five years you’re doing real, real well. Let’s back up. As distributors, we’re a sales organization. Never mind that we’ve got five shops where we do repairs and customization and in some cases manufacturing a couple of products. But basically, we’re a sales organization. We want to have as much of our resources as possible in sales and customer interaction and try to automate the backroom stuff as much as possible. In a sales role you have to know what you’re selling. I don’t think you can teach a work ethic. You can certainly lead by example and you can use people as examples.” Hiring people is expensive he says, you don’t want to make a mistake. “What I find happens here is that some of the managers are so anxious to fill an empty slot that they either intentionally or unintentionally overlook some obvious characteristics,” he admits before adding that reading people is tough. “I’m not part of the recruiting process, but sometimes I get a kick at the can to interview a candidate and what I try to do is lay out the job, the responsibility as honestly as I can, don’t sugar coat it, and see the reaction to that.” You have to take the time to win their trust, he says, “and if someone wants to be helped they have to be willing to be critiqued. If they don’t, well, I can’t help you.”

The Revolving Relationship Door

The other challenge? Relationships. “They are as important today as they ever were,” he says. “The problem today is that there are more and more large companies, particularly on the supplier side. A lot of these companies are multi-national and that means two things. One is that the decision making authority is not local and the other thing it means is that the players are changing quickly. Somebody gets parachuted in and is responsible for Canada and maybe it’s a three year run and they are off to something else and you have to start over building the relationship.”

The impact of an ever-changing people scene is that those people may not understand their business, Shapiro says. “They may not understand the roots of our business or the extent of loyalty over an extended period of time. We really spend a lot of time sharing with our suppliers, not the least of which is our roots, but how we think and what we think. We share a lot of information with our suppliers that I know many distributors do not and the reality is that we are in the middle of a supply chain and we need our suppliers as much as we need our customers. The better they understand that the better they understand our capabilities or non-capabilities, and the better that relationship can be.”

But sometimes you lose by default, he says. “Some of those customers are multi-national as well. So you got multi-nationals using the products of multi-nationals and you’ve got behaviours and relationships that are out of sight and we don’t know what those relationships are like in other parts of the world between that multi-national customer and that multi-national supplier.”

Shapiro attributes much of the company’s success to being involved in trade associations. Franklin Empire is currently a member of Electro-Federation Canada and Affiliated Distributors. They first joined CEDA in 1976, an organization that he went on to chair.

“We were a very small distributor when I came into it and I would not have ordinary crossed paths with the national chains. We were different worlds. My relationship with CEDA and Electro-Fed allowed me to meet all those people. I knew all the decision makers in the industry whether I did business with them or not via that. Union Electric, the company my father worked for, went out of business in ’93. And Union were the largest, even when they went bankrupt, and they choose not to be part of the industry trade association because they thought that the fees were too high and they weren’t getting their money’s worth. So the net result was they are no longer around and I attribute our position in the marketplace to that, to the relationships that either began or got reinforced as being part of a trade association.”

People, relationships, they are all challenges. But don’t mistake a challenge for worry. Asked if there are any other worries on his radar, Shapiro responds: “We don’t worry, that’s not our style. You play the hand you’re dealt the best you can and if you do more right than wrong on a consistent basis, you’re going to come right side up.”